Welsh Annals

The earliest surviving version of the Latin Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales) is found in Harleian MS 3859. The annals, immediately followed by a set of Welsh royal genealogies, are interpolated into a version of the Historia Brittonum. The manuscript itself dates from c.1100 (the corruption of Welsh names and words suggests that it was not produced in Wales), but the last entry in the annals corresponds to the year 954. The genealogies begin with Owain ap [son of] Hywel Dda (Hywel died in 950, and Owain in 988), who ruled in South Wales (Deheubarth), and it is likely that both the annals and the genealogies belong to Owain’s time.

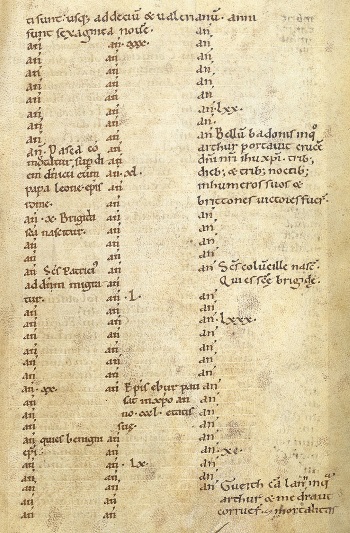

The origins of the Annales Cambriae appear to lie in St Davids (Mynyw), Dyfed. It seems that from around 800 contemporary records were kept at St Davids, but for earlier entries other sources were used – predominantly Irish and North British. The first entry corresponds to the year 453. The word ‘corresponds’ is used because these terse annals do not actually quote dates. The sporadic entries are made on a framework of years – each year marked only by an’ (short for annus). Every tenth year is additionally identified with a Roman numeral (though some decades have nine years, some eleven). Although the first entry corresponds to 453, the framework begins at the equivalent of 445, and, although the last entry corresponds to 954, the framework extends to the equivalent of 977.[*] The significance of the start date is not clear, but it seems that the framework is based on the Easter cycle of 532 years. The Harleian MS 3859 version is the A-text of the Annales Cambriae. The B-text and C-text exist in late-13th century manuscripts.

The B-text was written, probably at the Cistercian abbey of Neath, on the flyleaves of an abbreviated edition of the Domesday Book (National Archives MS E.164/1). The text begins with a world-history section, ultimately derived from the work of Isidore of Seville (d.636). The framework of years – each year marked by anus (sic), with no separate indication of decades – begins with Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain,[*] though the Isidoran contribution continues up to the reign of Emperor Leo I (457–73). There are a few entries taken from Geoffrey of Monmouth, but there are also a few seemingly genuine entries not found in the A-text.[*] From 1097 until the final entry, in 1286, Anno Domini dates are attached to the annals.

The C-text (British Library MS Cotton Domitian A i) was produced at St Davids. It too begins with an Isidoran section, with British references inserted, which continues to the reign of Emperor Heraclius (610–41). Thereafter, the framework of years – each year marked by annus, with no separate indication of decades – emerges, and continues to the equivalent of 1289 (the last entry actually appears against the previous annus – corresponding to 1288). The influence of the imaginative pen of Geoffrey of Monmouth is apparent up to 734.[*]

The A-text is, by almost two centuries, the most ancient surviving version of the Annales Cambriae, but it was not used as a source by the B-text or the C-text. Up until 1202 (after which point they diverge), the B-text and C-text seem to be developments of a St Davids text that had been independently derived from an ancestor of the A-text.[*]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the frameworks of the three texts do not stay in register with each other, and none of them stays in register with a chronological framework derived from external sources. As a result, deducing accurate dates from the Annales Cambriae is something of an inexact science.

A related source is the Brut y Tywysogion (Chronicle of the Princes), which exists in several manuscripts that, basically, represent three Welsh language versions of a lost original Latin text that was compiled, probably at the Cistercian abbey of Strata Florida, in the late-13th century. Based on the Annales Cambriae, but with additional material, this Latin text was apparently conceived as a continuation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae. One version of the Brut y Tywysogion is known after, its representative, the Red Book of Hergest (Oxford, Jesus College MS 111). Another after Peniarth MS 20. In the third version, though, the Welsh material is combined with material from English sources, and this is independently titled Brenhinedd y Saesson (Kings of the Saxons).