Supplement

Addenda to East Anglia

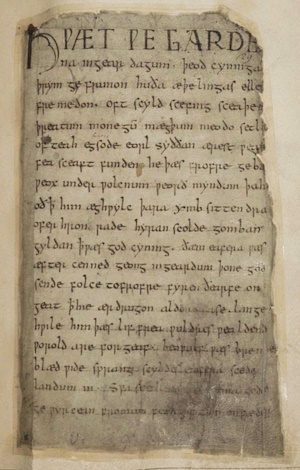

Beowulf

The epic poem Beowulf, which is written in Old English (Anglo-Saxon), is so-called after its hero (the original is not titled). The single extant manuscript survived, though not unscathed, a fire, on Saturday 23rd October 1731, in Ashburnham House (now part of Westminster School), where the library of manuscripts collected by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571–1631) was housed. It is now in the British Library (British Library MS Cotton Vitellius A xv). The manuscript was produced around the year 1000 (by two scribes), but its story is set in the 6th century – at what stage between those dates the work was originally composed is the subject of scholarly debate.

Heorot, the mead-hall of Hrothgar, king of the Danes, has been terrorized for twelve years by Grendel, a seemingly invincible monster. Beowulf, of the Geats, hears of Hrothgar’s plight, and sails to his aid.[*] Beowulf fights Grendel with his bare hands, and tears the monster’s arm off. Grendel, fatally wounded, retreats to his lair to die. Seeking revenge, Grendel’s mother attacks Heorot. Beowulf tracks her down, and, after a great struggle, slays her with an ancient giant’s sword. Beowulf becomes king of the Geats, and rules for fifty peaceful years. Then, a fire-breathing dragon, angry that some of its treasure has been stolen, begins to ravage his kingdom. The aged Beowulf, with the assistance of a faithful warrior, Wiglaf, kills the dragon, but is fatally wounded. With his dying breaths he nominates Wiglaf as his successor. Beowulf’s body is burned, and his ashes are buried, with much treasure, in a mound on a high headland.

The Martyrdom of King Æthelberht

In 794: “Offa, king of the Mercians, commanded the head of King Æthelberht to be struck off”. So says Manuscript A of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the earliest extant source to report Æthelberht’s demise, written about a century after the event. Though the language of the Chronicle is Old English, Æthelberht is titled ‘king’ in Latin (i.e. rex). Manuscripts B, C, D and E simply have Æthelberht’s name, with no title, so it seems that a copyist in the line of transmission ending in Manuscript A has seen fit to add the title in Latin, which might possibly indicate that he was aware of the king from a Latin saint’s ‘Life’ (Vita). If so, it would mean that Æthelberht was the object of a cult by the late-9th century. A half-century later he was certainly being venerated as a saint. Theodred, bishop of London (and, seemingly, also of a diocese based on Hoxne in Suffolk), willed estates “to God’s community at St Æthelberht’s church at Hoxne” (S1526). Theodred died around 951. Another will, drawn up for one Wulfgeat of Donnington (S1534), shows that Hereford Cathedral was dedicated to St Æthelberht by around 1000.

The earliest source purporting to provide details of Æthelberht’s fatal encounter with Offa is an anonymous ‘Life’ – or rather a ‘Passion’ (Passio), since he was seen as a martyr – surviving in an early-12th century manuscript.[*] In a nutshell, the story it tells is that Æthelberht, king of East Anglia, sought to marry a daughter of Offa, king of Mercia. He travelled to Offa’s palace at Sutton (presumably Sutton Walls, near Hereford[*]) to make his proposal. Offa, however, had heard a rumour that Æthelberht was intending to invade his kingdom. He was persuaded by his wife, Cynethryth, that the rumour was indeed true, and to offer a handsome reward to anyone who would kill Æthelberht. One Winberht volunteered for the task. Æthelberht was taken captive, tortured, and finally beheaded with his own sword. Offa had his remains dumped in a marsh by the River Lugg. With the assistance of miraculous lights, the remains were recovered and buried at Fernley, which became Hereford, where, in due course, a monastery, precursor of the cathedral, was built by Milfrith, an otherwise unknown king of an unnamed distant region. This anonymous, Hereford version, of Æthelberht’s martyrdom – Æthelberht and Offa were both Christians, but his execution was nevertheless regarded as a martyrdom – had been reworked, successively, by Osbert of Clare and Giraldus Cambrensis, by the end of the 12th century.

The abbey of St Albans claimed to have been founded by Offa. They developed their own version of the Æthelberht story, in which their founder is shown to be an innocent party. The early-13th century chronicler Roger of Wendover, a monk at St Albans, writes, s.a. 792:

Æthelberht, king of the East-Angles, son of King Æthelred, left his territories, much against his mother’s remonstrances, and came to Offa, the most potent king of the Mercians, beseeching him to give him his daughter in marriage. Now Offa, who was a most noble king, and of a most illustrious family, on learning the cause of his arrival, entertained him in his palace with the greatest honour, and exhibited all possible courtesy, as well to the king himself as to his companions. On consulting his queen Quendritha, and asking her advice on this proposal, she is said to have given her husband this diabolical counsel, “Lo,” said she, “God has this day delivered into your hands your enemy, whose kingdom you have so long desired; if, therefore, you secretly put him to death, his kingdom will pass to you and your successors forever.” The king was exceedingly disturbed in his mind at this counsel of the queen, and, indignantly rebuking her, he replied, “Thou hast spoken as one of the foolish women; far from me be such a detestable crime, which would disgrace myself and my successors;” and having so said, he left her in great anger. Meanwhile, having by degrees recovered from his agitation, both the kings sat down to table, and, after a repast of royal dainties, they spent the whole day in music and dancing with great gladness. But in the meantime, the wicked queen, still adhering to her foul purpose, treacherously ordered a chamber to be adorned with sumptuous furniture, fit for a king, in which Æthelberht might sleep at night. Near the king’s bed she caused a seat to be prepared, magnificently decked, and surrounded with curtains; and underneath it the wicked woman caused a deep pit to be dug, wherewith to effect her wicked purpose. When king Æthelberht wished to retire to rest after a day spent in joy, he was conducted into the aforesaid chamber, and, sitting down in the seat that has been mentioned, he was suddenly precipitated, together with the seat, into the bottom of the pit, where he was stifled by the executioners placed there by the queen; for as soon as the king had fallen into the pit, the base traitors threw on him pillows, and garments, and curtains, that his cries might not be heard; and so this king and martyr, thus innocently murdered, received the crown of life which God hath promised to those that love him. As soon as this detestable act of the wicked queen towards her son-in-law was told to the companions of the murdered king, they fled from the court before it was light, fearing lest they should experience the like fate. The noble king Offa, too, on hearing the certainty of the crime that had been wrought, shut himself up in great grief in a certain loft, and tasted no food for three days. Nevertheless, although he was counted guiltless of the king’s death, he sent out a great expedition, and united the kingdom of the East Angles to his dominions. St Æthelberht was ignominiously buried in a place unknown to all, until his body, being pointed out by a light from heaven, was found by the faithful and conveyed to the city of Hereford, where it now graces the episcopal see with miracles and healing powers.