THIRD-CENTURY CRISIS

In 235, Emperor Alexander Severus was murdered by mutinous soldiers, at Moguntiacum (modern-day Mainz), on the Rhine.[*] The mutineers hailed their commander – a common man who had risen through the ranks – emperor. He is known as Maximinus Thrax (r. 235–238), and his elevation to the purple marks the beginning of a half-century of upheaval in the Roman Empire – a period characterised by:

- A rapid turnover of emperors, many of whom rose out of the ranks of the army (the term ‘barracks emperors’ is sometimes used), nearly all of whom met violent deaths.

- Almost uninterrupted warfare, both civil and foreign.

- Monetary collapse – the silver coinage was almost totally debased by the 260s.

The, so-called, ‘third-century crisis’ draws to a close with the accession of Diocletian in 284. In the middle of this tumultuous period, in 260, Britain became part of a breakaway empire known as:

The Gallic Empire

Valerian had become undisputed emperor in 253 – his rival, Aemilian, having been killed by his own troops after a reign of only three months. Rome’s frontiers were threatened on all sides – the main antagonists being the Franks, the Alamanni, the Goths, and the Persians. Valerian immediately shared power with, his adult son, Gallienus – Valerian assumed responsibility for the eastern half of the Empire, Gallienus the western half.

emp100

Aurelius Victor, Liber de Caesaribus, evidently completed in 360/61.

Eutropius, Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita, apparently composed 369/70.

Anonymous, Epitome de Caesaribus, compiled (on the face of it ) in 395.

The enigmatic Historia Augusta, probably written round-about 400.And two Greek-written sources:

Zosimus, New History, seemingly written c.500.

Zonaras, Epitome of Histories, early-12th century.The Latin story and the Greek story are sometimes contradictory. The two Byzantine historians, Zosimus and Zonaras, preserve snippets of Dexippus of Athens, who wrote soon after 270. The Latin sources, which, with one notable exception, carry only brief summaries of emperors’ reigns, chiefly draw on a single, mid-4th century, source, usually referred to as the Kaisergeschichte.[*] The exception is the Historia Augusta which, though usually following the Kaisergeschichte – directly, and indirectly via Aurelius Victor and Eutropius – also knows Dexippus, and is notorious for mischievously weaving an elaborate web of fantasy around a slim thread of history.[*]

In 260, whilst campaigning against the Persians, in Mesopotamia, Valerian was taken captive.

emp101

And presently Valerian also, in a mood alike frantic, lifted up his impious hands to assault God, and, although his time was short, shed much righteous blood.[*] But God punished him in a new and extraordinary manner, that it might be a lesson to future ages that the adversaries of Heaven always receive the just recompense of their iniquities. He, having been made prisoner by the Persians, lost not only that power which he had exercised without moderation, but also the liberty of which be had deprived others; and he wasted the remainder of his days in the vilest condition of slavery: for Sapores [Shapur I], the king of the Persians, who had made him prisoner, whenever he chose to get into his carriage or to mount on horseback, commanded the Roman to stoop and present his back; then, setting his foot on the shoulders of Valerian, he said, with a smile of reproach, “This is true, and not what the Romans delineate on board or plaster.” Valerian lived for a considerable time under the well-merited insults of his conqueror; so that the Roman name remained long the scoff and derision of the barbarians: and this also was added to the severity of his punishment, that although he had an emperor for his son, he found no one to revenge his captivity and most abject and servile state; neither indeed was he ever demanded back. Afterward, when he had finished this shameful life under so great dishonour, he was flayed, and his skin, stripped from the flesh, was dyed with vermilion, and placed in the temple of the gods of the barbarians, that the remembrance of a triumph so signal might be perpetuated, and that this spectacle might always be exhibited to our ambassadors, as an admonition to the Romans, that, beholding the spoils of their captived emperor in a Persian temple, they should not place too great confidence in their own strength.According to Aurelius Victor (§32) Valerian died, having being “cruelly mutilated”, soon after, i.e. in the same year as, his capture, “while still a robust old man” (Valerian was probably in his mid-60s at the time he was captured). Both Eutropius (IX, 7) and the Epitome de Caesaribus (§32), however, using the same words, state that Valerian was captured and “grew old in ignominious servitude” – the Epitome adds that the Persian king: “was accustomed, with him bent low, to place his foot on his shoulders and mount his horse.” In the imaginative Historia Augusta (‘The Two Gallieni’ 8–9), ‘Trebellius Pollio’ tells a whimsical tale in which Valerian’s son Gallienus (who is presented as a depraved incompetent by Aurelius Victor, Eutropius and, particularly, the Historia Augusta) puts-on a procession in Rome. Amongst the crowd there was “loud lamentation for the father whom the son had left unavenged”. In the procession were men playing the part of Persian captives:De Mortibus Persecutorum §5

… certain wits mingled with them and most carefully scrutinized all, examining with open-mouthed astonishment the features of every one; and when asked what they meant by that sagacious investigation, they replied, “We are searching for the Emperor’s father.” When this incident was reported to Gallienus, unmoved by shame or grief or filial affection, he ordered the wits to be burned alive …Anyway, Zosimus (I, 36) says that, having been captured, Valerian: “ended his days in the capacity of a slave among the Persians, to the disgrace of the Roman name in all future times.” Zonaras (XII, 23): “[Valerian] ended his life in Persia, reviled and mocked as a captive.” None of these sources mention the supposed flaying.

At the same time, although he was strenuously attempting to drive the Germans out of Gaul, Licinius Gallienus [i.e. Valerian’s son] hurriedly descended on Illyricum. There at Mursa [Osijek, in eastern Croatia] he defeated Ingenuus, the governor of Pannonia, who had conceived a desire to be emperor after learning of Valerian’s disaster, and subsequently Regalianus, who had renewed the war after rallying the soldiers who had survived the disaster at Mursa.[*]Aurelius Victor Liber de Caesaribus §33

emp102

At that time too, a force of Alamanni took possession of Italy while tribes of Franks pillaged Gaul and occupied Spain, where they ravaged and almost destroyed the town of Tarraconensis [Tarragona], and some, after conveniently acquiring ships, penetrated as far as Africa.Eutropius (IX, 7) says that “the Germans [the Alamanni] advanced as far as Ravenna”. Zosimus (I, 37–38), however, says that “the Scythians … penetrated Italy as far as Rome”. Presumably, when Zosimus says “Scythians”, usually meaning the Goths, he actually means the Alamanni. At any rate, Zosimus goes on to say that Gallienus “continued beyond the Alps, intent on the German war [against the Franks, presumably]”, so the senate scraped together an ad hoc army which scared off the “barbarians”, who then “ravaged all the rest of Italy”. Eventually, Gallienus went “to Rome to relieve Italy from the war which the Scythians were thus carrying on”. Zonaras (XII, 24) says that Gallienus defeated 300,000 Alamanni, at Milan, with a force of just 10,000. An inscription (L’ Année épigraphique 1993, 1231), on an altar found at Augsburg (in Roman times: Augusta Vindelicum, capital of the province of Raetia) in 1992, celebrates the defeat of a band of Juthungi (a group associated with the Alamanni) in the April of … well the indicated year is another subject of debate, but probably 261. The inscription notes that “many thousand Italian captives were freed”, so the Juthungi must have been returning home from a raid on Italy. No doubt Gallienus took a considerable number of troops from the Rhine frontier to confront Ingenuus. It would seem reasonable to suggest that the Alamanni and the Franks took advantage, and managed to penetrate deep into the Empire.[*] Incidentally, the mention of the Franks by Aurelius Victor, above, is their first appearance in history.Liber de Caesaribus §33

During his absence, Gallienus had left his son, the Caesar Saloninus, in nominal charge.[*] Saloninus was under the guardianship of one Silvanus (or Albanus), whilst the army was under the command of Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus.

… [Postumus] was inclined towards innovation, and accompanied some soldiers that revolted at the same time to Agrippina [Cologne], which is the principal city on the Rhine, in which he besieged Saloninus, the son of Gallienus, threatening to remain before the walls until he was given up to him. On this account the soldiers found it necessary to surrender both him and Silvanus, whom his father had appointed his guardian, both of whom Postumus put to death and made himself sovereign of the Celtae [i.e. Gauls].Zosimus New History I, 38

emp103

Albanus [Zosimus’ Silvanus], when he had learned this, sent messengers and demanded that the plunder be brought to him and to the young Gallienus [i.e. Saloninus]. Postumus called his soldiers together and exacted from them their shares of the plunder, scheming to incite them to rebellion. And that is exactly what happened. With them he attacked the city of Agrippina, and the inhabitants of the city surrendered to him both the son of the sovereign and Albanus, and he executed them both.In their accounts of the time of Postumus’ rebellion, Aurelius Victor, the Historia Augusta (in the persona of Trebellius Pollio) and Zosimus name Gallienus’ son Saloninus. Zonaras says the youth was called Gallienus, like his father – on this point though, ‘Trebellius Pollio’ notes:Epitome of Histories XII, 24

With regard to his name there is great uncertainty, for many have recorded that it was Gallienus and many Saloninus.To add to the confusion, the Epitome de Caesaribus (§32) implies that it was Gallienus’ son Valerian who was killed during Postumus’ rebellion. Though the Epitome says that Postumus came to power when Gallienus’ son was killed, it does not say he was executed by Postumus. Zosimus and Zonaras, however, are explicit on that point. Aurelius Victor doesn’t mention that Saloninus was killed, and Eutropius, in his brisk résumé, mentions no son of Gallienus at all. Gallienus had two sons, Valerian and Saloninus, who consecutively held the rank of Caesar. An inscription from Mauretania (CIL VIII, 8473), evidently set-up before Valerian Augustus had been taken prisoner by the Persians, commemorates the “deified Caesar” Valerian, brother of the “most noble Caesar” Saloninus – i.e. Valerian Caesar was dead at the time of the inscription, and Saloninus was Caesar. Evidence from Egypt – Alexandrian coinage and papyri from Oxyrhynchus – indicates Valerian Caesar died in 258. The same sources suggest that Saloninus died in 260–61. Most modern scholars, it seems, agree that Postumus rebelled in 260, after news of the capture of Valerian Augustus arrived in Gaul, and that it was Saloninus who was killed. Rare coins, minted in Gaul (possibly at Cologne), show that Saloninus had assumed the rank of Augustus. According to Aurelius Victor, Eutropius and the Historia Augusta, once his father was out of the way, Gallienus neglected his duties and indulged in debauchery – it was as a result of Gallienus’ behaviour that Postumus rebelled.[*] The two Greek-writers, however, give no indication that this was the case, indeed, Zonaras (XII, 25) praises Gallienus’ character. In the Historia Augusta, ‘Trebellius Pollio’ conjures up a tale in which Gallienus is “the evil prince”, and Postumus is cast as the hero:Historia Augusta ‘The Two Gallieni’ 19

If anyone, indeed, desires to know the merits of Postumus, he may learn Valerian’s opinion concerning him from the following letter which he wrote to the Gauls: “As general in charge of the Rhine frontier and governor of Gaul we have named Postumus, a man most worthy of the stern discipline of the Gauls. He by his presence will safeguard the soldiers in the camp, civil rights in the forum, law-suits at the bar of judgement, and the dignity of the council chamber, and he will preserve for each one his own personal possessions; he is a man at whom I marvel above all others and well deserving of the office of prince, and for him, I hope you will render me thanks. If however, I have erred in my judgement concerning him, you may rest assured that nowhere in the world will a man be found who can win complete approval…”Valerian’s glowing testimonial is, without doubt, a fabrication.Historia Augusta ‘Thirty Tyrants’ 3

Now while Gallienus, continuing in luxury and debauchery, gave himself up to amusements and revelling and administered the commonwealth like a boy who plays at holding power, the Gauls, by nature unable to endure princes who are frivolous and given over to luxury and have fallen below the standard of Roman valour, called Postumus to the imperial power; and armies, too, joined with them, for they complained of an emperor who was busied with his lusts.‘Trebellius Pollio’ refuses to associate any dishonourable conduct with, his knight in shining armour, Postumus:Historia Augusta ‘The Two Gallieni’ 4

This man, the most valiant in war and most steadfast in peace, was so highly respected for his whole manner of life that he was even entrusted by Gallienus with the care of his son Saloninus (whom he had placed in command of Gaul), as the guardian of his life and conduct and his instructor in the duties of a ruler.[*] Nevertheless, as some writers assert – though it does not accord with his character – he afterwards broke faith and after slaying Saloninus seized the imperial power. As others, however, have related with greater truth, the Gauls themselves, hating Gallienus most bitterly and being unwilling to endure a boy as their emperor, hailed as their ruler the man [i.e. Postumus] who was holding the rule in trust for another, and despatching soldiers they slew the boy.Historia Augusta ‘Thirty Tyrants’ 3

(•)

(•)

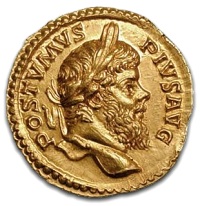

POSTVMVS PIVS AVG

(Postumus Pius Augustus)[*]

… Postumus, a man of very obscure birth, assumed the purple in Gaul, and held the government with such ability for ten years, that he restored the provinces, which had been almost ruined, by his great energy and judgement.Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 9

Inscriptions show that the British provinces, the Spanish provinces and, for a short time at least, the province of Raetia, were also part of the, so-called, Gallic Empire, which Postumus organized in proper Roman style, with its own senate and consuls.[*] It would appear that he never attempted to expand his empire further.[*]

Gallienus, when he had learned of these things, proceeded against Postumus, and, when he had engaged him, was initially beaten and then prevailed, with the result that Postumus fled. Then Aureolus was sent to chase him down. Though able to capture him, he was unwilling to pursue him for long, but, coming back, he said that he was unable to capture him. Thus Postumus, having escaped, next organized an army.Zonaras Epitome of Histories XII, 24

At some point, Gallienus again marched against Postumus. He besieged him in an unnamed city in Gaul, but received an arrow wound in the back and was obliged to abandon the siege. He clearly never achieved a decisive victory over Postumus.

Probably in 267, whilst Gallienus was occupied in the Balkans with the Goths and their associates, the previously mentioned Aureolus:

… since he was in command of the legions in Raetia,[*] had seized the imperial power …Aurelius Victor Liber de Caesaribus §33

He [Aureolus] seized the city of Mediolanum [Milan] and prepared to engage the sovereign.[*] The latter, too, when he had arrived with a force and taken the field against the usurper, destroyed many of the opposition. Then Aureolus was wounded and penned in Mediolanum, besieged by the sovereign.Zonaras Epitome of Histories XII, 25

In 268 (late-summer?), whilst he was besieging Aureolus in Milan, Gallienus was assassinated. One of the officers (probably) involved in the murder plot, Claudius, was proclaimed emperor (Claudius II, generally called Claudius Gothicus, a title gained as a result of his success against the Goths). During his occupation of Milan, Aureolus had minted coins in Postumus’ name. If he was expecting Postumus to come to his aid, he was disappointed. Following Gallienus’ murder, Aureolus was also despatched. Postumus had problems of his own:

After he had driven off a horde of Germans he was involved in a war with Laelianus whom he routed just as successfully, but he then perished in a revolt of his own men [around spring 269] supposedly since he had refused to allow them, despite their insistence, to plunder the inhabitants of Mogontiacum [Mainz] because they had supported Laelianus.Aurelius Victor Liber De Caesaribus §33

With Postumus and Laelianus both dead, the purple was assumed by Marius, a former blacksmith. Numismatic evidence suggests he lasted rather longer than the two or three days the Latin sources allot him.[*] Next to rule was Victorinus, but the Gallic Empire was beginning to crumble. Inscriptions suggest that Spain shifted its allegiance to Claudius Gothicus. Mentions in later panegyrics and a poem by Ausonius testify that, after a siege of seven months, Victorinus suppressed a rebellion by the denizens of Augustodonum (Autun, in east central France). Victorinus was:

… a man of great energy; but, as he was abandoned to excessive licentiousness, and corrupted other men’s wives, he was assassinated at Agrippina [Cologne] in the second year of his reign …Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 9

Extremely rare coins indicate that, for only a very short time, one Domitianus was Gallic Emperor. Numismatists place his brief rule after Victorinus, but it is not mentioned in the literary sources.[*] Aurelius Victor says:

… Victoria, after the loss of her son Victorinus, bought the approval of the legions with a large sum of money and made Tetricus emperor. He was of a noble family and was serving as governor of Aquitania, and the title and trappings of Caesar were bestowed upon his son, Tetricus.Aurelius Victor Liber De Caesaribus §33

… [Tetricus] was chosen emperor in his absence, and assumed the purple at Burdigala [Bordeaux]. He had to endure many insurrections among the soldiery.Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 10

It was probably about mid-271 that Tetricus became ruler of the Gallic Empire. Meanwhile, in the legitimate Empire (sometimes called the Central Empire), Claudius Gothicus had died of natural causes – a plague – in 270. Claudius was succeeded by his brother Quintillus. Aurelian, one of the officers involved in the plot that had brought Claudius to power, soon declared against Quintillus. The dispute didn’t come to warfare however. Quintillus was either killed or committed suicide, and Aurelian was undisputed emperor:

That man was not unlike Alexander the Great or Caesar the Dictator; for in the space of three years he retook the Roman world from invaders …Epitome de Caesaribus §35

In 274 Aurelian turned his attention to the Gallic Empire:

He overthrew Tetricus at Catalauni [Châlons-sur-Marne] in Gaul. Tetricus himself, indeed, betraying his own army, whose constant mutinies he was unable to bear; and he had even by secret letters entreated Aurelian to march towards him, using, among other solicitations, the verse of Vergil:

“Unconquer'd hero, free me from these ills.”Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 13

Tetricus was displayed, in Rome, at Aurelian’s triumph, but, in a final twist:

This Tetricus was afterwards governor of Lucania [in southern Italy], and lived long after he was divested of the purple.Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 13

The Gallic Empire was no more. Britain had been loyal to it throughout.[*]

Aurelian was murdered in 275. There followed a short interregnum before Tacitus (said to be seventy-five years old) was chosen as his successor. Tacitus reigned for some six months before he too was murdered (probably), and his half-brother, the Praetorian prefect Florian, assumed the purple. The army in the East, though, hailed their commander, Probus, emperor. The opposing factions met at Tarsus. Apparently, Florian’s army, being mainly composed of Europeans, suffered from the extreme heat. Only a few skirmishes were fought; Florian was killed by his own soldiers,[*] having reigned for just a couple of months.

Probus ruled from 276 to 282:

… a man rendered illustrious by the distinction which he obtained in war. He recovered Gaul, which had been seized by the Barbarians, by remarkable successes in the field.Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 17

… [Probus] fought some fierce battles, first against the Longiones, a German nation, whom he conquered …

Another of his battles was against the Franks, whom he subdued through the good conduct of his commanders. He made war on the Burgundians and the Vandals… All of them that were taken alive were sent to Britain, where they settled, and were subsequently very serviceable to the emperor when any insurrection broke out.Zosimus New History I, 67–68

He also suppressed, in several battles, some persons that attempted to seize the throne, namely Saturninus in the east, and Proculus and Bonosus at Agrippina [Cologne].[*]Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 17

He likewise suppressed an insurrection in Britain, by means of Victorinus, a Moor, who had persuaded him to confer the government of Britain upon the leader of the insurgents [name unknown]. Having sent for Victorinus, and rebuked him for his advice, he sent him to appease the disturbance; who going presently to Britain, took off the traitor by a stratagem.Zosimus New History I, 66

In 282, Probus was killed at Sirmium (his birthplace; then in Pannonia Inferior; now Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) by his own men, who had, seemingly, switched their support to, his Praetorian prefect, Carus.

emp104

When he [Probus] had come to Sirmium, desiring to enrich and enlarge his native place, he set many thousand soldiers together to draining a certain marsh, planning a great canal with outlets flowing into the Save, and thus draining a region for the use of the people of Sirmium. At this the soldiers rebelled, and pursuing him as he fled to an iron-clad tower, which he himself had reared to a very great height to serve as a look-out, they slew him there …Once again, ‘Flavius Vopiscus’ also knows the Greek story:Historia Augusta ‘Probus’ 21

I am not unaware that many have suspected and, in fact, have put it into the records that Probus was slain by the treachery of Carus. This, however, neither the kindness of Probus toward Carus nor Carus’ own character will permit us to believe …Historia Augusta ‘Carus, Carinus & Numerian’ 6

… [Carus] was clothed in the imperial robe and his sons, Carinus and Numerian, became Caesars. And since all the barbarians had seized the opportunity to invade once they had learned of the death of Probus, he sent his elder son to defend Gaul and, accompanied by Numerian, he straightway proceeded to Mesopotamia because that land is, so to speak, a customary cause of war with the Persians.Aurelius Victor Liber De Caesaribus §38

In 283, during a successful campaign against the Persians, Carus suddenly died. Carinus and Numerian continued to rule, as co-emperors. Carinus (or an officer despatched by him) apparently had military success in Britain, since both he and his brother acquired the title Britannicus Maximus.[*] Numerian was murdered, on the journey back to Europe, in 284, and the army declared a Dalmatian guards officer called Diocles emperor. Diocles took the name Diocletian. Carinus, pausing to suppress the rebellion of one Julianus, at Verona, marched against Diocletian. The two armies met, in 285, in modern-day Serbia. Carinus’ larger army was apparently at the point of victory when he was murdered by his own men, leaving Diocletian as the undisputed emperor.

emp105

… and he used to say that Diocletian, after slaying him, shouted, “Well may you boast, Aper, ‘’Tis by the hand of the mighty Aeneas you perish’ [Virgil Aeneid X, 830].”Once again, Zonaras (XII, 30) also offers an alternative, plainly wrong, version of Numerian’s demise, that “some record” – John Malalas (XII, 35) gives this version – Numerian’s forces were defeated by the Persians; Numerian was captured; he was flayed, and his skin made into a bag. Clearly a confusion between Valerian and Numerian. None of the sources has a good word to say about Carinus. Aurelius Victor:Historia Augusta ‘Carus, Carinus & Numerian’ 13

… when Carinus reached Moesia he straightway joined battle with Diocletian near the Margus [now Morava], but while he was in hot pursuit of his defeated foes he died under the blows of his own men because he could not control his lust and used to seduce many of his soldiers’ wives.Eutropius notes that Carinus was the object of “the utmost hatred and detestation”, and in his “great battle” against Diocletian he was:Liber De Caesaribus §39

… betrayed by his own troops, for though he had a greater number of men than the enemy, he was altogether abandoned by them between Viminacium and mount Aureus.‘Flavius Vopiscus of Syracuse’ alleges that, after the deaths of his father and brother, Carinus “committed acts of still greater vice and crime”, but makes no mention of any treachery by Carinus’ own men:Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 20

… he fought many battles against Diocletian, but finally, being defeated in a fight near Margus, he perished.The anonymous Epitomator doesn't mention any battle, but says that Carinus, who “defiled himself with all crimes”:Historia Augusta ‘Carus, Carinus & Numerian’ 10

… was tortured to death chiefly by the hand of his tribune, whose wife he was said to have violated.Oddly, Zonaras writes that Carinus:Epitome de Caesaribus §38

… living in Rome, presented a menace to the Romans, since he had become brutal, cruel and vindictive. He was killed by Diocletian, who had come to Rome.Incidentally, John Malalas (XII, 36) has Carinus conducting a successful campaign against the Persians, to avenge his brother’s death, during which he dies of natural causes!Epitome of Histories XII, 30